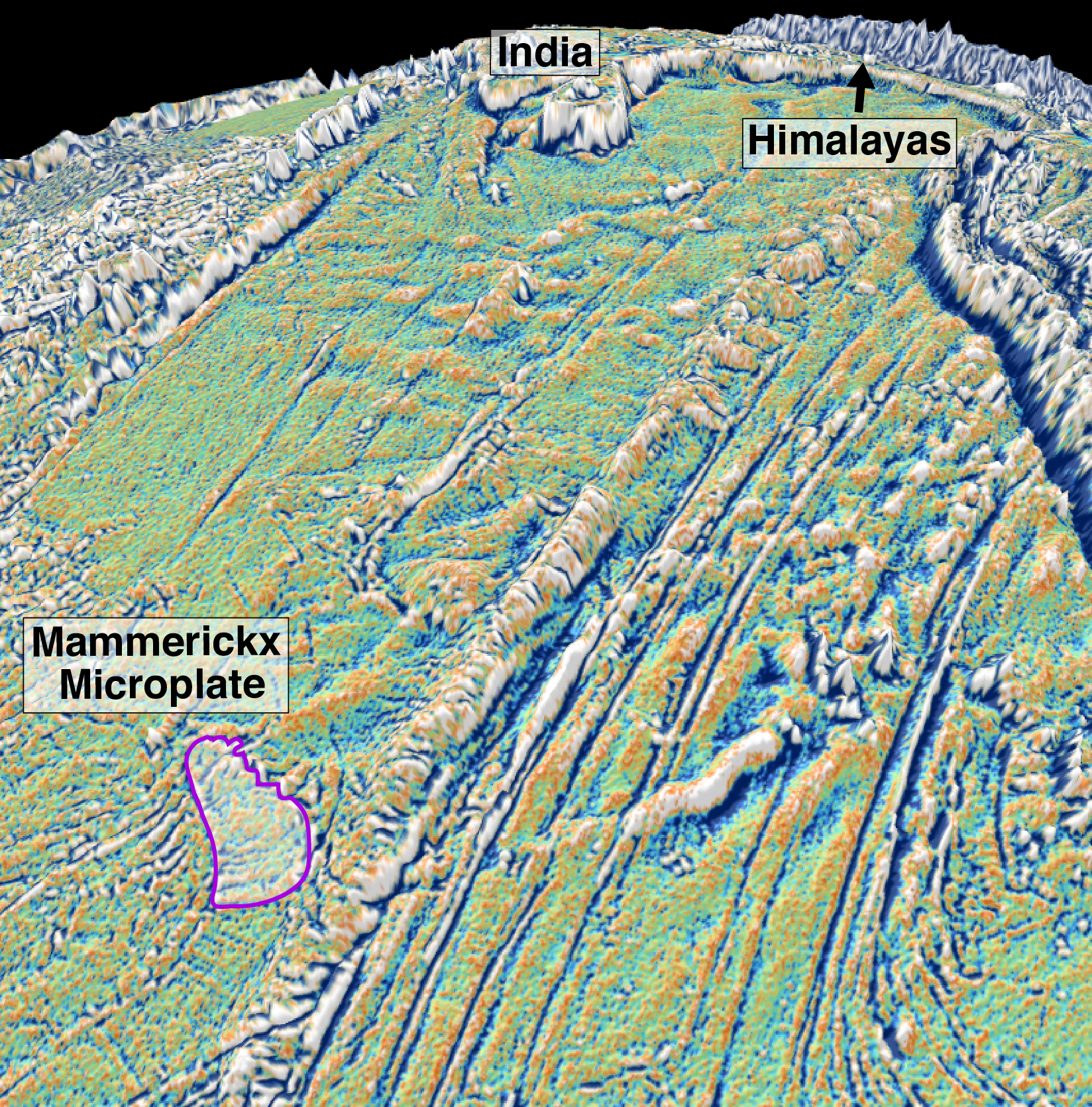

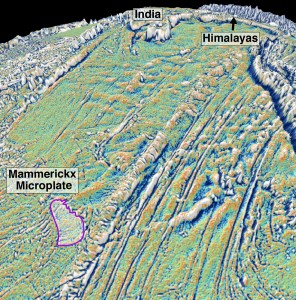

An international team of scientists led by the University of Sydney’s School of Geosciences has discovered that the crustal stresses caused by the initial collision between India and Eurasia cracked the Antarctic Plate far away from the collisional zone and broke off a fragment the size of Tasmania in a remote patch of the central Indian Ocean.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Sydney’s School of Geosciences has discovered that the crustal stresses caused by the initial collision between India and Eurasia cracked the Antarctic Plate far away from the collisional zone and broke off a fragment the size of Tasmania in a remote patch of the central Indian Ocean.

The ongoing tectonic collision between the two continents produces enormous geological stresses that build up along the Himalayas and lead to numerous earthquakes every year – but now scientists have unravelled how stressed the Indian Plate became 47 million years ago when its northern edge first collided with Eurasia.

50 million years ago India was travelling northwards at speeds of around 15 cm/yr – close to the plate tectonic speed limit. Soon after it slammed into Eurasia crustal stresses along the mid-ocean ridge between India and Antarctica intensified to breaking point. A chunk of Antarctica’s crust broke off and started rotating like a ball bearing, creating a newly discovered tectonic plate.

The microplate, named the ‘Mammerickx Microplate’ after Dr Jacqueline Mammerickx, a pioneer in seafloor mapping, is significant because its formation helps pinpoint exactly when the initial collision between India and Eurasia occurred.

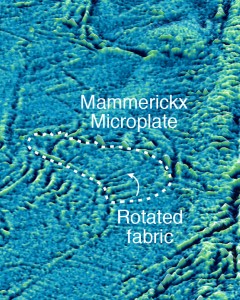

The discovery was made using satellite radar beam mapping from space, which measures the bumps and dips of the sea surface caused by water being attracted by submarine mountains and valleys, combined with conventional marine geophysical data.

Why is this important? Lead-author Dr. Matthews explains: “The age of the largest continental collision on Earth has long been controversial, with age-estimates ranging from at least 59 to 34 million years ago. Knowing this age is particularly important for understanding the link between the growth of mountain belts and major climate change.”

The Mammerickx Microplate rotation, revealed in a fanning abyssal hill pattern in satellite radar images, records a sudden increase in crustal stress, dating the birth of the Himalayan Mountain Range to 47 million years ago.

The Mammerickx Microplate rotation, revealed in a fanning abyssal hill pattern in satellite radar images, records a sudden increase in crustal stress, dating the birth of the Himalayan Mountain Range to 47 million years ago.

Co-author Prof. Müller said: “Dating this collision requires looking at a complex set of geological and geophysical data, and no doubt discussion about when this major collision first started will continue, but we have added a completely new, independent observation, which has not been previously used to unravel the birth of this collision. It is beyond doubt that the collision must have led to a major change in India’s crustal stress field; that’s why the plate fragmentation we mapped is a bit like a smoking gun for pinning down the collision age”.

Co-author Prof. Sandwell from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography added: “We may think that the great age of Earth’s exploration and discovery is over, as humans have been to even the remotest corners of the continents and mapped their geography, geology and ecology – what’s left to discover? Our microplate discovery shows that the same does not hold for our ocean basins”.

Dr. Matthews adds: “We now have more detailed maps of Pluto than we do of most of our own planet, and that’s because about 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered with water. Roughly 90% of the seafloor is uncharted by ships and it would take 200 ship-years of time to make a complete survey of the deep ocean outside continental shelves at a cost of between 2 and 3 billion US Dollars – that’s why advances in comparatively low-cost satellite technology are the key to charting the deep, relatively unknown abyssal plains.”

The findings from this study have been published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

![]()